Preservation isn’t enough; this document must be seen, studied and understood.

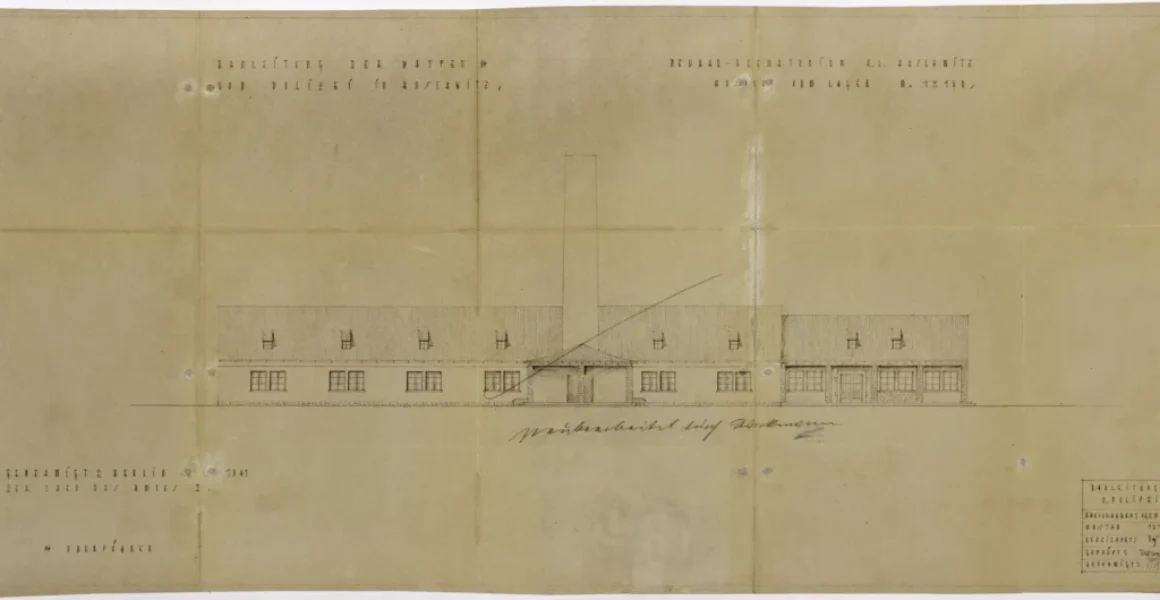

When I first saw the faded whiteprint, an architectural drawing of the earliest design concept for what became Crematoria II and III at Auschwitz-Birkenau, I felt the crushing weight of evil. This piece of paper with its neat geometric lines—so professional, so precise—was proof of the intent to incinerate the corpses of hundreds of thousands of Jewish men, women and children who would be murdered on an industrial scale.

I have dedicated much of my philanthropic work to support Jewish organizations and to combat antisemitism. I knew immediately that this artifact had to be brought to light, especially in our era of surging Holocaust denial and resurgent antisemitism.

That’s why I acquired the whiteprint for $1.5 million, a sum chosen to honor the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

The document, drawn by SS architect Walter Dejaco in October 1941, has been authenticated by Robert Jan van Pelt, one of the world’s leading experts on Auschwitz. Van Pelt has called it “quite literally irreplaceable.”

The whiteprint represents crucial architectural evidence of Nazi extermination infrastructure. It is a tangible link to the systematic planning behind the Holocaust and an irrefutable record of genocidal intent. Physical artifacts such as this provide enduring evidence of the Nazi pursuit of the “Final Solution.”

Yet preservation by itself isn’t enough. The whiteprint must be seen, studied and understood.

For that reason, I intend to exhibit it at various Holocaust museums and institutions dedicated to fighting antisemitism before permanently donating it to one such institution. Each viewing will be an opportunity to educate, to remember and to inoculate future generations against denial and distortion.

The proceeds from the acquisition will support an early-childhood curriculum designed to combat extremism and hate before they take root. By emphasizing altruism and empathy in young children, we can build immunity against the dehumanization that makes hatred and ultimately violence possible.

‘A particular responsibility’

The whiteprint acquisition is part of a broader commitment.

Working with the Counter Extremism Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, I helped fund the purchase of the former home of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss. At 88 Legionów Street in Oświęcim, Poland, the house sits directly adjacent to the camp where he oversaw mass murder on a scale that will forever be incomprehensible.

CEP has transformed the house into the Auschwitz Research Center on Hate, Extremism and Radicalization (ARCHER) at House 88, which uses the very latest technology to disrupt the shadowy financial networks that extremists use to foment antisemitism, extremism and terrorism. What was once the home of a principal architect of genocide now houses scholars, researchers and activists working to fight against the mainstreaming of the evil Höss embodied. I serve as co-chair of the Fund to End Antisemitism, Extremism and Hate, which helps enable ARCHER’s vital work.

We are living in a time of acute danger. Antisemitic incidents have reached levels not seen in generations. Holocaust denial proliferates online, often cloaked in the dishonest guise of “just asking questions,” as it edges ever closer to the mainstream—a harrowing development. The survivors who bore witness to history’s greatest crime will not be alive much longer. And when they are gone, artifacts like the whiteprint, Holocaust museums and organizations like ARCHER will become our primary vehicles for transmitting memory and combating lies.

The Jewish philanthropic community carries a particular responsibility. We cannot shirk it. We must support education that cultivates moral responsibility and seriousness; fund research that exposes and disrupts contemporary forms of antisemitism; preserve and display evidence of the Holocaust (in addition to the Hamas-led terrorist attacks in Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, the most devastating massacre since the Holocaust); and build communal institutions that will outlast our lifetimes.

We must confront the most dangerous form of contemporary antisemitism: the systematic delegitimization of the State of Israel.

We must push back against those who accuse Israel of committing genocide, a modern-day blood libel that was once confined to the fringes of radical academia, but has escaped containment into the broader discourse around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

We must proudly support Israel and champion a strong U.S.-Israel relationship. We can differ in our views of particular Israeli policies, but we must never lose sight of what is at stake: the survival and security of the world’s only Jewish state, home to nearly half the Jews on the planet.

For a small people—there are only about 16 million Jews in the world today, fewer than on the eve of World War II—this work is not optional.

Elie Wiesel moved beyond vowing “Never Again” in his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, insisting instead: “Sometimes, we must interfere.”

Fighting antisemitism must be a sustained commitment expressed through action, scholarship and memory.

Elliott Broidy is an entrepreneur who has used his extensive experience and talent to found, invest in, and in some cases, manage as CEO, more than 160 companies over his four-decade career. He has given extensively to support the Jewish community and other causes during his career. He currently is the Co-Chair of the Fund to End Antisemitism, Extremism and Hate which supports the Auschwitz Research Center on Hate, Extremism and Radicalization (ARCHER) at House 88, an initiative of The Counter Extremism Project.