Boca Raton Couple Preserve a Chilling Document As A Reminder Of The Holocaust’s Dark Path

This piece originally appeared in Boca Daily News on December 23, 2025.

By Daniel Nee

As Hanukkah concludes, and menorahs are being dutifully stored away for another year, shining light toward the darkest corners of humanity has rarely seen a time of more importance than the present. Just before the start of a holiday season that became marred by a terrorist attack on a sunny beach in Australia, canceled celebrations in Europe and fears of future tragedies reaching the shores of United States, one Boca Raton couple made it their mission to preserve a disturbing-but-powerful document that shows the literal pencil-to-paper plotting of evil, drawn up as a group of men gathered to discuss a macabre final solution.

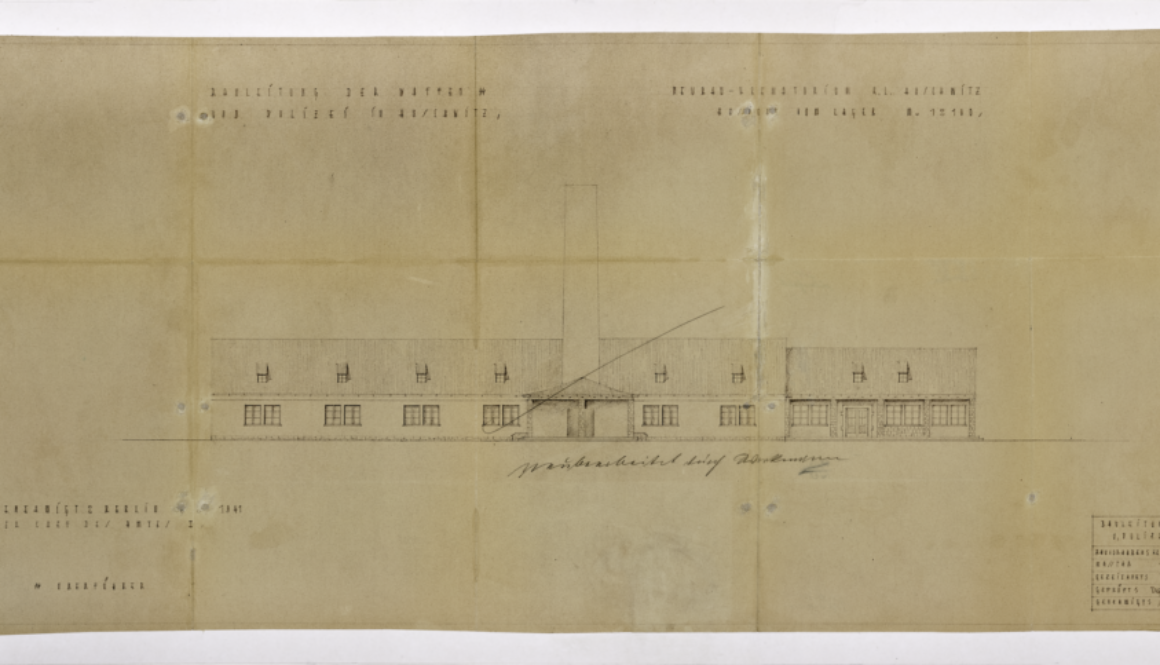

Elliott Broidy, 68, has experienced a celebrated career straddling the worlds of defense, diplomacy and philanthropy. A pioneer in leveraging open source intelligence to improve safety and security, he and his wife, Robin, have acquired a rare, real, tangible object that would have made world leaders of the 1940s shudder at the thought of what was being planned. The landscape-style document, a few feet long, set forth a way to manage the horrors of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp: a physical whiteprint of Crematoria II and III, where the bodies of those whose lives were stolen in the Holocaust would be disposed.

The Broidys acquired the document in exchange for a $1.5 million commitment to efforts that will go toward developing anti-hate and anti-extremism curricula for children. The figure represents the 1.5 million children who were killed in the Holocaust.

The historic document was produced by SS architect Walter Dejaco on Oct. 24, 1941, in preparation for days of meetings in which the logistics of killing at an industrial scale were to be discussed in bureaucratic fashion. Under the leadership of camp commandant Rudolf Höss, two whiteprints were drawn up – one which is locked away in an archive in Moscow, having been seized by Soviet soldiers after the fall of the Nazi regime, and the other which resurfaced in the mid-2010s. The authenticity of the document was in question until it was examined by Dutch professor and Auschwitz historian Robert Jan van Pelt, who linked together the timeline of the meetings of Nazi officials, the location of the document’s origin, and the date of its physical creation, which directly corresponded to the conference led by Höss.

“This is about education,” Robin Broidy said. “Especially for young people. If you understand how this happened once, you’re less likely to accept it happening again.”

One of only two known surviving copies of the original whiteprint of the crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau. (Elliott Broidy)

In a world where it is becoming increasingly difficult to tell if photos and stories are real or the machinations of artificial intelligence platforms, human-authenticated documents such as the crematorium plans provide concrete – rather than theoretical – examples of what extremism can lead to.

“There are still Holocaust deniers in the world,” said Elliott Broidy. “We consulted experts to authenticate the document and learned that only two copies exist — one in Moscow that hasn’t been seen since 1991, and this one. We felt it was important for the public to see it. When the Nazis retreated, they destroyed much of Birkenau and burned many documents. But they forgot the architectural office. That’s why we still have proof of what these buildings were designed for.”

Based on the date of its creation, the planning document was drawn up for what has become known as the Wannsee Conference, the physical meeting of Nazi political and military leadership that produced plans to deport European Jews to facilities in occupied Poland where they would be killed. The result of the conference, named for the Berlin suburb where it was held, is clear. But documents such as the whiteprint help drive home the personal reality of its intent – real people, real plans and real decisions on how to perpetrate a genocide at scale. The plans represented an expansion of a camp that held Soviet POWs to what became the most infamous venue of the Holocaust.

“It shows the earliest planning stages of industrialized mass murder,” said Broidy. “That’s why it’s historically priceless.”

The Broidy family, who relocated to Boca Raton from California to be closer to family and enjoy a more peaceful daily life, have become more active in causes that battle antisemitism and extremism in recent years. With colleagues, they purchased the residential “house next door” to Auschwitz where Höss lived with his family. Photos in the Broidy’s personal collection show parties, children’s birthday celebrations, and joyous gatherings occurring with the death camp’s guard towers and exterior walls in the background. The house – which was the subject of the award-winning 2023 film The Zone of Interest – was acquired as a guarantee not only that history would be preserved, but so it would never become a deranged shrine to what happened mere yards away. The whiteprint added to the context of the prior purchase.

“History may not repeat itself exactly, but hatred persists,” said Robin Broidy. “This document shows how ordinary people were manipulated into participating in evil. It forces people to ask: ‘Am I being manipulated the same way?’”

“If it gives people pause — if it reminds them that this was planned, intentional, and real — then it serves a purpose,” she added.

The physical document has been shipped to a secured location in California where the facilities exist to preserve a sketch that is more than eight decades old, printed on what resembles yellowed newsprint. Its ultimate destination is to be determined – it may find a home at the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., on the grounds of the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum in Poland, or another facility with preservation infrastructure. There is a chance, if feasible, that it could be transported to remote locations, giving a larger number of people an opportunity to experience the chilling sight with their own eyes.

“Our rabbi [in California] wanted the proceeds from the project to go toward education, but asked that the document be released,” Broidy said. “He, and we, felt it was important for the public to see it, though ultimately it should rest somewhere that can preserve it properly. While I didn’t have direct relatives affected in the Holocaust, I met many survivors and children of survivors.”

“Over the past few years, antisemitism became a very urgent issue for us,” Elliott Broidy said. “This was the best symbol, the best way to actively combat antisemitism, we could find.”